2. Nervous Tissue

Nervous tissue is composed of two types of cells, neurons and glial cells. Neurons are responsible for the computation and communication that the nervous system provides. They are electrically active and release chemical signals to communicate between each other and with target cells. Glial cells, or glia or neuroglia, are much smaller than neurons and play a supporting role for nervous tissue. Glial cells maintain the extracellular environment around neurons, improve signal conduction in neurons and protect them from pathogens. Ongoing research also suggests that glial cell number matches neuron number and that they even can send signals themselves.

Neuron Anatomy

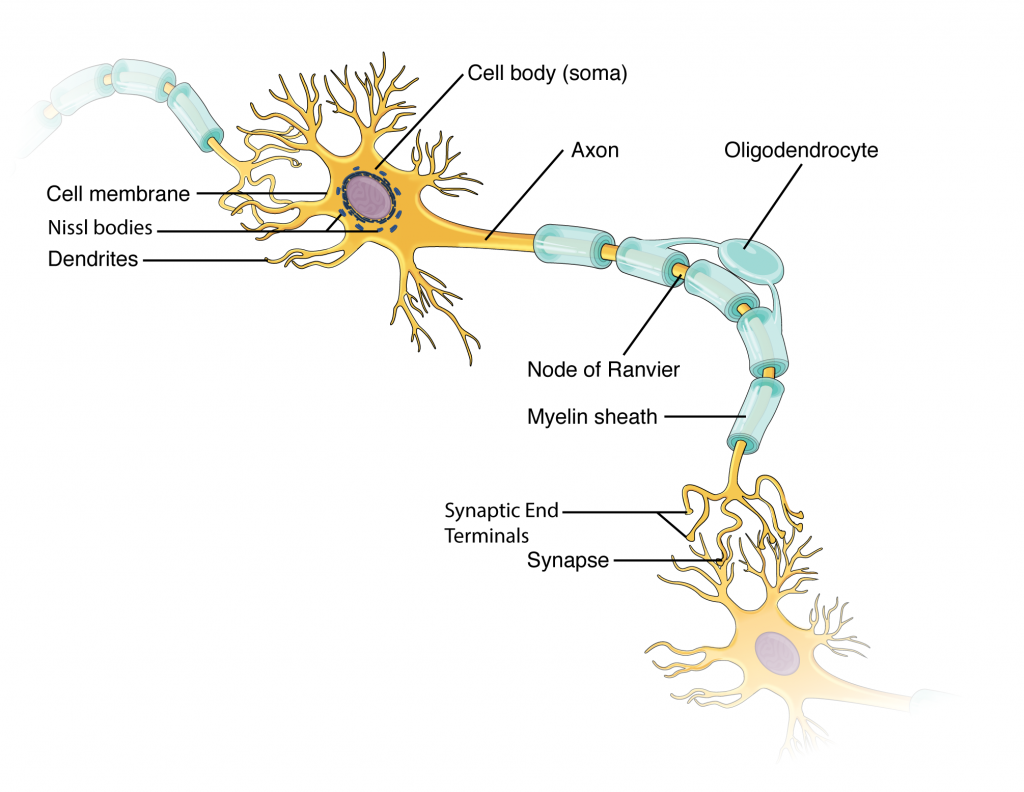

Neurons are nucleated cells with specialized structural properties. Some neurons have a single long extension (axon) that reaches great distances, others are very small, star shaped cells without obvious axons (See Figure 2.1 – add to image the term axon, reference cells without one).

Though neuron shapes vary greatly, every neuron houses its nucleus in a region known as the cell body (also called soma) from which cellular activity like repair or cell membrane recycling is controlled. Associated with the nucleus, neurons also have many rough endoplasmic reticula, called Nissl bodies (these can be seen in neurons using a light microscope). The nucleus, Nissl bodies and golgi apparatuses together produce the many ion channels and pumps that reside in the cell membrane. These transmembrane proteins are neccessary for neurons to send electrical signals (graded potentials and action potentials, see section 12.4). In addition, neurons consume much ATP and typically have many mitochondria.

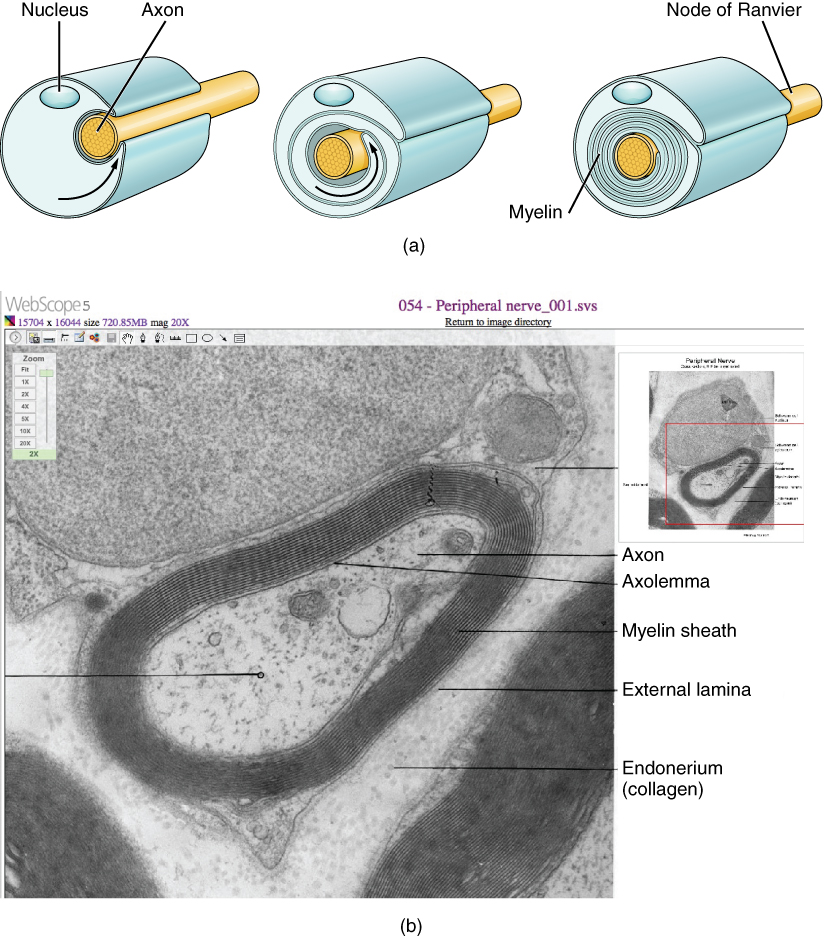

In Figure 2.2, the cell body shows both many short projections and one long projection emerging from the cell body. These short projections are dendrites which receive most of the input from other neurons or stimuli in the extracellular environment; the location of the dendrites on the neuron marks the receptive region of the neuron. Dendrites are usually highly branched processes, providing locations for other neurons to communicate with the neuron. Neurons have polarity—meaning that information flows in one direction through the neuron. In the figure 12.2.2 neuron, information flows from the dendrites, across the cell body, and down the large axon emerging from the cell body at the axon hillock (axon hillock is an anatomical term to describe where the cell body and axon meet). The first section of the axon where an action potential is generated is called the initial segment. In multipolar and bipolar neurons, the initial segment is found at the axon hillock (see Figure 2.3). However, in unipolar neurons, the initial segment is not found at the axon hillock, and can actually be located many inches or even a few feet from it near the dendrites (see Figure 2.3)! However, in unipolar neurons, the initial segment is not found at the axon hillock, and can actually be located many inches or even a few feet from it! Often axons are wrapped by myelin sheaths, leaving exposed sections (node of Ranvier) between segments of myelin. Myelin is produced by oligodendrocytes (glial cells) in the CNS and Schwann cells in the PNS; it acts as electrical insulation, speeding information conduction down the neuron. Once information reaches the terminal end of this neuron, it is transferred to another cell. The site of communication between a neuron and its target cell is called a synapse. The terminal end has several branches, each with a synaptic end bulb to store chemicals needed for communication with the next cell. Figure 2.2 shows the relationship of these parts to one another.

Types of Neurons

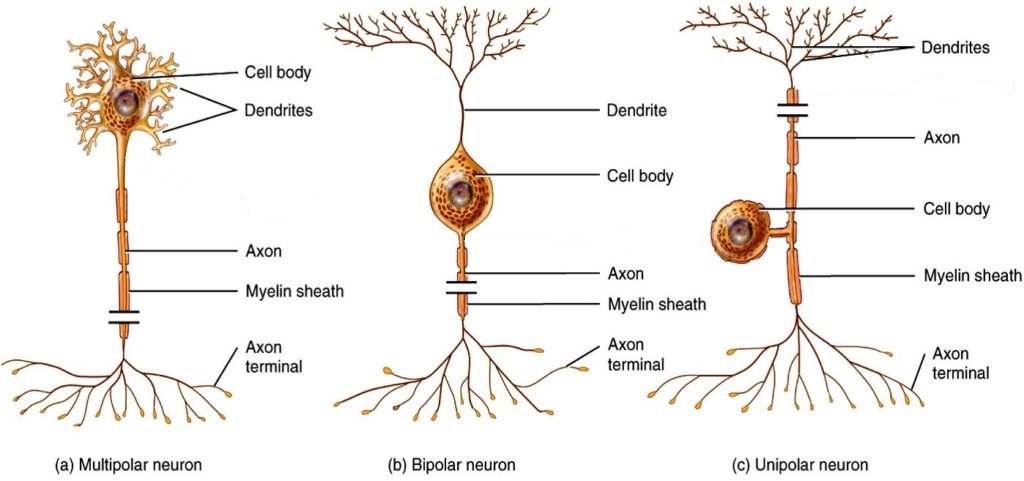

There are trillions of neurons in the nervous system and cell shape can vary widely. Three common shapes of neurons are shown in Figure 2.3.

Multipolar neurons have multiple processes emerging from their cell bodies (hence their name, multipolar). They have dendrites attached to their cell bodies and often, one long axon. Motor neurons are multipolar neurons, as are many neurons of the CNS.

Bipolar cells have two processes, which extend from each end of the cell body, opposite to each other. One is the axon and one the dendrite. Bipolar cells are not very common. They are found mainly in the olfactory epithelium (where smell stimuli are sensed), and as part of the retina in the eye.

Unipolar cells have one long axon emerging from the cell body, with the cell body located between the two ends, and off to the side. At one end of the axon are dendrites, and at the other end, the axon forms synaptic connections with a target cell. Unipolar cells are exclusively sensory neurons and have their dendrites in the periphery where they detect stimuli. Their cell bodies are typically found in ganglia of the peripheral nervous system.

Glial Cells

There are six types of glial cells. Four of them are found in the CNS and two are found in the PNS. Figure 2.4 outlines some common characteristics and functions.

Glial Cells of the CNS

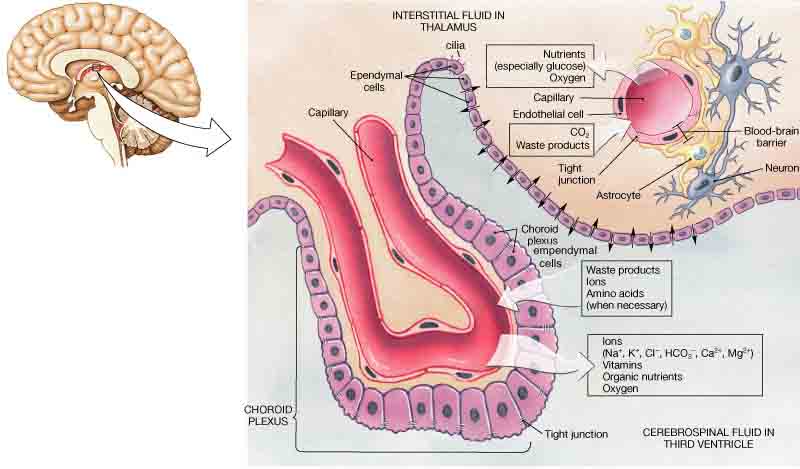

One cell providing support to neurons of the CNS is the astrocyte, so named because it appears to be star-shaped under the microscope (astro- = “star”, cyte = “cell”). Astrocytes have many processes extending from their main cell body (not axons or dendrites like neurons, just cell extensions). Those processes extend to interact with neurons, blood vessels, or the connective tissue covering the CNS (Figure 2.4). Generally, they are supporting cells for the neurons in the central nervous system. Some ways in which they support neurons in the central nervous system are by maintaining the concentration of chemicals in the extracellular space, removing excess signaling molecules, reacting to tissue damage, and inducing to the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The blood-brain barrier is a protective physiological barrier that keeps many substances that circulate in the blood from getting into the central nervous system, restricting what can cross from circulating blood into the CNS. Usually, blood vessels are leaky because there are gaps between the cells of the vessel walls. These gaps permit rapid movement of molecules out of the blood into the extracellular space around tissue cells, delivering nutrients and hormones. However, the neurons of the brain may be affected by rapid, regular changes in extracellular concentrations preventing signal transmission. To prevent such fluctuations, astrocytes release compounds to the blood vessels, inducing tight junctions between the otherwise leaky blood vessel cells. When the BBB is intact, nutrient molecules, such as glucose or amino acids, must now pass through the vessel cells of the BBB by transcellular processes (using membrane proteins). Small, fat soluble molecules (respiratory gases, alcohol) are able simply diffuse through the cell membranes, but other large, water soluble molecules cannot. The highly restrictive permeability of the BBB may restrict drug delivery to the CNS. Pharmaceutical companies are challenged to design drugs that can cross the BBB as well as have an effect on the nervous system.

Also found in CNS tissue is the oligodendrocyte, sometimes called just “oligo,” which is the glial cell type that insulates axons in the CNS. The name means “cell of a few branches” (oligo- = “few”; dendro- = “branches”; -cyte = “cell”). There are a few processes that extend from the cell body. Each one reaches out and surrounds an axon to insulate it in myelin. One oligodendrocyte will provide the myelin for multiple axon segments, either for the same axon or for separate axons. The function of myelin will be discussed below.

Microglia are, as the name implies, smaller than most of the other glial cells. Ongoing research into these cells, although not entirely conclusive, suggests that they may originate as white blood cells, called macrophages, that become part of the CNS during early development. While their origin is not conclusively determined, their function is related to what macrophages do in the rest of the body. When macrophages encounter diseased or damaged cells in the rest of the body, they ingest and digest those cells or the pathogens that cause disease. Microglia are the cells in the CNS that can do this in normal, healthy tissue, and they are therefore also referred to as CNS-resident macrophages.

Ependymal cells filter blood to make cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the fluid that circulates through the CNS. CSF is needed in the brain to provide nutrients, remove wastes and create a stable extracellular environment because the BBB is so restrictive. In each of the brain cavities (ventricles), ependymal cells surround the blood vessels forming choroid plexuses. These choroid plexuses filter specific components of the blood to produce cerebrospinal fluid. Everyday they produce enough CSF to fill a pint glass! Though the BBB is absent in the choroid plexuses, the ependymal cells there are connected to each other by tight connections, forming a highly restrictive boundary. More ependymal cells line the ventricles and use their cilia to help move the CSF through the ventricular space. The relationship of these glial cells to the structure of the CNS is seen in Figure 2.4.

Glial Cells of the PNS

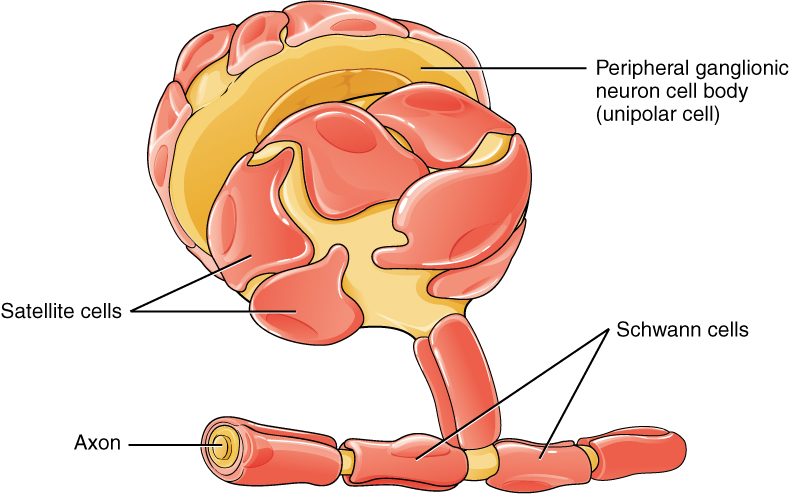

One of the two types of glial cells found in the PNS is the satellite cell. Satellite cells surround the cell bodies of neurons in the PNS. They provide support, performing similar functions in the periphery as astrocytes do in the CNS—except, of course, for establishing the BBB.

The second type of glial cell is the Schwann cell, which insulate axons with myelin in the periphery. Schwann cells are different than oligodendrocytes in that a Schwann cell wraps around a portion of only one axon segment and no others. Oligodendrocytes have processes that reach out to multiple axon segments, whereas the entire Schwann cell surrounds just one axon segment. The nucleus and cytoplasm of the Schwann cell are on the edge of the myelin sheath. The relationship of these two types of glial cells to ganglia and nerves in the PNS is seen in Figure 2.5.

Myelin

Oligodendrocytes in the CNS and Schwann cells in the PNS provide myelin. Whereas the manner in which either cell is associated with the axon segment, or segments, that it insulates is different, the means of myelinating an axon segment is mostly the same in the two situations. Myelin is a lipid-rich sheath that surrounds the axon and by doing so creates a myelin sheath that facilitates the transmission of electrical signals along the axon. Simply, myelinated axons send signals faster than unmyelinated axons. The lipids of myelin are essentially the phospholipids of the glial cell membrane. Myelin, however, is more than just the membrane of the glial cell. It also includes important proteins that are integral to that membrane. Some of the proteins help to hold the layers of the glial cell membrane closely together.

The appearance of the myelin sheath can be thought of as similar to the pastry wrapped around a hot dog for “pigs in a blanket” or a similar food. The glial cell is wrapped around the axon several times with little to no cytoplasm between the glial cell layers. For oligodendrocytes, the rest of the cell is separate from the myelin sheath as a cell process extends back toward the cell body. A few other processes provide the same insulation for other axon segments in the area. For Schwann cells, the outermost layer of the cell membrane contains cytoplasm and the nucleus of the cell as a bulge on one side of the myelin sheath. During development, the glial cell is loosely or incompletely wrapped around the axon (Figure 2.6a). The edges of this loose enclosure extend toward each other, and one end tucks under the other. The inner edge wraps around the axon, creating several layers, and the other edge closes around the outside so that the axon is completely enclosed.

Myelin sheaths can extend for one or two millimeters, depending on the diameter of the axon. Axon diameters can be as small as 1 to 20 micrometers. Because a micrometer is 1/1000 of a millimeter, this means that the length of a myelin sheath can be 100–1000 times the diameter of the axon. Figure 2.2, Figure 2.4, and Figure 2.5 show the myelin sheath surrounding an axon segment, but are not to scale. If the myelin sheath were drawn to scale, the neuron would have to be immense—possibly covering an entire wall of the room in which you are sitting.

Disorders of the…Nervous Tissue

Several diseases can result from the demyelination of axons. The causes of these diseases are not the same; some have genetic causes, some are caused by pathogens, and others are the result of autoimmune disorders. Though the causes are varied, the results are largely similar. The myelin insulation of axons is compromised, making electrical signaling slower. In some cases, signaling stops, preventing muscles from responding and causing paralysis.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one such disease. It is an example of an autoimmune disease. The antibodies produced by lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) mark myelin as something that should not be in the body. This causes inflammation and the destruction of the myelin in the central nervous system. As the insulation around the axons is destroyed by the disease, scarring occurs. This is where the name of the disease comes from; sclerosis means hardening of tissue, as occurs in a scar. Multiple scars are found in the white matter of the brain and spinal cord. Control of the skeletal and smooth musculature is compromised, affecting not only movement, but also control of organs such as the bladder.

Guillain-Barré (pronounced gee-YAN bah-RAY) syndrome is an example of a demyelinating disease of the peripheral nervous system. It is also the result of an autoimmune reaction, but the inflammation is in peripheral nerves. Sensory symptoms or motor deficits are common, and autonomic failures can lead to changes in the heart rhythm or a drop in blood pressure, especially when standing, which causes dizziness.